Fathers of the Corvette

Harley Earl

Harley Earl is the father of the Corvette. The Corvette was his idea pure and simple. He was influenced after World War II

watching Jaguars and MG's run road-racing courses like Watkins Glen. He felt America needed its own sports car and he

convinced GM to develop its own, inexpensive two-seater.

Harley Earl is the father of the Corvette. The Corvette was his idea pure and simple. He was influenced after World War II

watching Jaguars and MG's run road-racing courses like Watkins Glen. He felt America needed its own sports car and he

convinced GM to develop its own, inexpensive two-seater.

Originally code named "Project Opel", Earl kept the Corvette program pretty much to himself. He had a special small studio

with a handful of people working on it. At the time, Earl wasn't sure which GM division ought to sell the Corvette, But he

felt close to Ed Cole at Chevrolet and decided to give the "Bowtie Division" first shot. Cole was sold the first time he saw

the prototype. He knew it was just what the stodgy Chevrolet division needed.

The Corvette debuted at Motorama in New York, January of 1953 and was an instant hit. Six months later the Corvette went into

production and the rest is history. But the Corvette may not have been Earl's greatest achievement. His main accomplishment was

making automotive design an institution. It was the work of Harley Earl that put the sizzle back into the American car business

after World War II. His expressive designs defined an entire era. He was the first man to design a car with a wraparound

windshield, cars without running boards, and the first to tantalize the motoring public with dream cars like the 1938 Y Job

and the 1951 Le Sabre.

The Corvette debuted at Motorama in New York, January of 1953 and was an instant hit. Six months later the Corvette went into

production and the rest is history. But the Corvette may not have been Earl's greatest achievement. His main accomplishment was

making automotive design an institution. It was the work of Harley Earl that put the sizzle back into the American car business

after World War II. His expressive designs defined an entire era. He was the first man to design a car with a wraparound

windshield, cars without running boards, and the first to tantalize the motoring public with dream cars like the 1938 Y Job

and the 1951 Le Sabre.

He grew up in Hollywood in the early 1900s and quickly developed designs with a flare for the dramatic. His father ran a

custom coach building company, and young Harley was put to work- as Chief Designer. He would often produce clay models for

customers, showing them what their future vehicles would look like. Earl later became close friends with Lawrence Fisher, who

became president of the Cadillac Division of General Motors in 1925. Fisher asked Earl for some design help on the new LaSalle.

His successful design caught the attention of GM Chairman Alfred B. Sloan.

Harley moved to Detroit in 1927 and quickly set about making GM one of the world leaders in design. In 1937, his Art and

Color department was renamed General Motors Design Staff. Among Earl's most memorable designs are the Chevy Nomad, the Cadillac

Eldorado Brougham, all of the early 1950s Buicks and of course, the Corvette. Earl's legacy, however is the Corvette which will

live on as a testimony to his vision and his talent. Harley Earl died on April 10, 1969.

Harley Earl takes delivery of the first 1953 Corvette to be built on June 30, 1953

Actually, much of the 1953 model-year's run of 300 cars would be hand-built, as more-efficient production processes for

assembling the vehicle's fiberglass body were still being perfected. All cars would be built the same way so workers could

concentrate on putting the bodies together properly without being rushed and without the distraction of trim and equipment

variations. As a result, all '53 Corvettes were painted Polo White and had Sportsman Red interiors, black tops, 6.70 X 15 four-ply

whitewall tires, Delco signal-seeking radios, and recirculating hot-water heaters. Also standard was a complete set of analog

instruments, including a 5000-rpm tachometer and a counter for total engine revolutions.

Actually, much of the 1953 model-year's run of 300 cars would be hand-built, as more-efficient production processes for

assembling the vehicle's fiberglass body were still being perfected. All cars would be built the same way so workers could

concentrate on putting the bodies together properly without being rushed and without the distraction of trim and equipment

variations. As a result, all '53 Corvettes were painted Polo White and had Sportsman Red interiors, black tops, 6.70 X 15 four-ply

whitewall tires, Delco signal-seeking radios, and recirculating hot-water heaters. Also standard was a complete set of analog

instruments, including a 5000-rpm tachometer and a counter for total engine revolutions.

The first Corvette to come off the assembly line was driven by Tony Kleiber, a Chevrolet body assembler, on June 30, 1953 --

just six months after its public unveiling as a Motorama dream car. Amazingly, the first production Corvette was changed little

from its concept display model. Yet at a suggested retail price of $3,513, the car had evolved into a considerably costlier

vehicle than the austere roadster Harley Earl had originally envisioned.

Zora Arkus-Duntov

Zora Arkus-Duntov didn't father the Corvette; he immortalized it.

Zora Arkus-Duntov didn't father the Corvette; he immortalized it.

Few knowledgeable enthusiasts say the name Corvette without a silent nod to its patron saint, Zora Arkus-Duntov.

While the Russian engineer often is incorrectly called the "father of the Corvette," its paternity belongs to Harley Earl,

the visionary who was the first head of General Motors' design staff. But it was Arkus-Duntov, a hot rodder at heart, who

took Earl's beautiful curved form and gave it a hard performance edge. Zora drove the Chevrolet Corvette into sports car

immortality while developing a racing pedigree to prove its credentials to the world.

Arkus-Duntov spent a career at GM as the consummate outsider, a maverick who was often misunderstood and not always aligned

with the business of producing high-volume automobiles for GM's volume division. But his personal ownership of the Corvette

program ensured its continued technical evolution and helped produce a halo vehicle for Chevrolet that would outlast

higher-volume Chevrolet nameplates.

Arkus-Duntov brought an unusual background into GM. The offspring of Russian revolutionaries, he witnessed the Russian Revolution

in 1917; was educated in one of Germany's top technical schools; joined the French Air Force; escaped from Nazi-occupied France;

caught a refugee ship to Ellis Island; consulted for top U.S. defense companies for the war effort; started his own munitions

operation in New York; helped develop an atomic compressor; entered his own car at Indianapolis; raced at Le Mans; and found his

way to GM, where he sought to use the resources of the largest company on Earth to build his kind of cars.

Arkus-Duntov brought an unusual background into GM. The offspring of Russian revolutionaries, he witnessed the Russian Revolution

in 1917; was educated in one of Germany's top technical schools; joined the French Air Force; escaped from Nazi-occupied France;

caught a refugee ship to Ellis Island; consulted for top U.S. defense companies for the war effort; started his own munitions

operation in New York; helped develop an atomic compressor; entered his own car at Indianapolis; raced at Le Mans; and found his

way to GM, where he sought to use the resources of the largest company on Earth to build his kind of cars.

Arkus-Duntov first saw a prototype of the Corvette on an auto show turntable in January 1953. He was so taken by the two-seater

that he applied for a job at GM. But after accepting a GM job a few months later, he may have thought he was making a deal with

the devil. GM was in the business of making money, not fine sports cars.

Arkus-Duntov's managers may have had similar misgivings about him. Sparks flew when his entrepreneurial, maverick style ran head

on into the conservative, blue-suit bureaucracy. Yet thanks to the influence of Ed Cole, Chevy's chief engineer, the volatile

combination brought an energy to GM that helped ignite some of its greatest sales successes in the 1960s and 1970s, a time when

GM's market share sometimes exceeded or approached 50 percent.

Off to the races

Arkus-Duntov started at GM in May 1953 and went to work in Chevrolet R&D under Maurice Olley. He was assigned minor tasks on the

first-generation Corvettes, but it wasn't long before he was envisioning a midengine configuration for the second generation. Just a

few months into the job, Arkus-Duntov wrote a memo entitled "Thoughts pertaining to youth, hot rodders and Chevrolet" that defined a

new approach to the performance youth market by the marketing of a performance parts catalog.

He also helped develop a mechanical fuel injection system along with Rochester Products' John Dolza that produced 1 hp for every cubic

inch of displacement.

Arkus-Duntov also pioneered Chevrolet's fledgling race program, starting off with several small-block V-8 performance demonstrations.

They included a record run up Pikes Peak in a Chevy 210 sedan and a run on Daytona Beach to set a Corvette speed record of 150 mph.

That led to factory racing efforts at Sebring and the construction of a purpose-built race car, the Corvette SS, which had its debut

and swan song during the same 1957 Sebring race. The SS was the victim of a new GM corporate policy that prohibited factory-sponsored

race programs.

Despite corporate policy, Arkus-Duntov kept the Corvette racing program going by developing high-performance packages available

to Corvette racers. He was also more than willing to provide whatever technical support he could, often at the cost of infuriating

his superiors.

His philosophy about production Corvettes was to make them as close to race cars as possible, a belief that ran against the

grain of more conservative factions at GM.

Arkus-Duntov developed several daring engineering concept cars, including several Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicles,

better known as CERV I and CERV II, which combined some of the most advanced thinking in

racing as well as influencing the engineering content of future Corvettes.

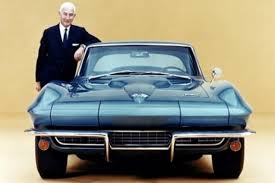

Arkus-Duntov's best chance to influence the production Corvette occurred with the second-generation Corvette Sting Ray

introduced in 1963. While the car represented a quantum leap in performance from previous Corvettes with its independent

rear suspension (from CERV I) and sophisticated powertrain, Arkus-Duntov had envisioned a sophisticated mid-engined Corvette

that would have been lighter, faster and much more responsive. But he found out the hard way that GM designer Bill Mitchell

really called the shots when it came to the look and configuration of Corvettes.

Risks and rewards

One of Arkus-Duntov's greatest triumphs involved one of his greatest risks -- the Corvette Grand Sport racing program.

As a way around the GM corporate racing program, he envisioned building 100 lightweight Corvettes that could be sold to

racing customers as a way to skirt the ban on factory racing.

One of Arkus-Duntov's greatest triumphs involved one of his greatest risks -- the Corvette Grand Sport racing program.

As a way around the GM corporate racing program, he envisioned building 100 lightweight Corvettes that could be sold to

racing customers as a way to skirt the ban on factory racing.

He rationalized the program in a memo to chief engineer Harry Barr: "As a national characteristic, Americans do not

like to be second-best, be it a space race or an auto race," Arkus-Duntov wrote. "Both are not individual, but rather

national contests. They in-volve technological ability of the national industry and with this, become a matter of personal pride.

If John Glenn's orbit makes all of us grow an inch taller, Corvette defeats in sports car racing make loads of people feel a

quarter of an inch smaller and the younger part of the population possibly more than that. I feel a winning car would enable

this vast group to grow a quarter of an inch taller and Chevrolet will have a new mass of grateful customers for all our

products -- cars, trucks and second-hand vehicles."

The Grand Sport program never got off the ground as Arkus-Duntov envisioned. But five cars were built that found their way

into the hands of racers with considerable under-the-table help from him -- and at great risk to his career. The pinnacle of

success was at Nassau in 1963 when three cars entered by Texas oil millionaire John Mecom -- and driven by a team that included

Dick Thompson, Jim Hall and Roger Penske -- beat the Shelby Cobras. Those five Grand Sport racers are among the most prized Corvettes.

The third-generation Cor-vette introduced in 1968 would represent Arkus-Dun-tov's last chance to build his midengined street car.

But Mitchell still held sway in terms of his preference for a long-hood, short-deck look, and the Corvette was becoming so successful

in the marketplace that Chevrolet was reluctant to change the formula.

Arkus-Duntov would continue developing midengine concept cars, leading up to the memorable Wankel-powered Aerovette, but he retired

in 1975 at the mandatory age of 65, having failed to achieve his midengined dreams. During his 22 years at GM, Arkus-Duntov succeeded

in something far greater: the immortalization of what might have been just another one-off concept car on the turntables at the GM Motorama.

Thanks in great measure to Arkus-Duntov, the Corvette is the longest running Chevy nameplate.

Plans are in place to honor Arkus-Duntov in his native Russia next year. A special exhibit in Moscow is being created by the Russian

Mini-stry of Culture as part of a series celebrating famous Russian expatriates.

Zora Arkus-Duntov might have been Louis Chevrolet's greatest alter ego. Both were fueled by a love of racing to make unforgettable

street cars, yet both were thwarted by conservative contemporaries who held their dreams in check. Yet both made themselves famous

by putting their foot on the throttle and never letting up.

Want to contact us? E-mail the Webmaster